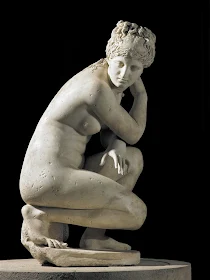

Μαρμάρινο άγαλμα

γυμνής Αφροδίτης. Ρωμαϊκό αντίγραφο, 2ος αι. μ.Χ. Royal Collection Trust/Her

Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, 2015.

Την

εξέλιξη των κανόνων του ωραίου στην αρχαία Ελλάδα και τις επιρροές τους

παρουσιάζει το Βρετανικό Μουσείο σε έκθεσή του, συγκεντρώνοντας εμβληματικά

αγάλματα που περιλαμβάνονται στη συλλογή του καθώς και «θαυμαστά» δάνεια από

άλλα μουσεία.

Ρωμαϊκό

αντίγραφο του περίφημου Δισκοβόλου του Μύρωνα, από τη συλλογή του Βρετανικού

Μουσείου. Nobility of nudity: a Roman copy of Myron’s 5th

century BC bronze discus-thrower (discobolus).

Με

τίτλο «Ο ορισμός του ωραίου: το σώμα στην

τέχνη στην αρχαία Ελλάδα», η έκθεση παρουσιάζει τις διάφορες απεικονίσεις

του σώματος στην αρχαία Ελλάδα.

Figure of a River

God, (circa 438-432BC) – one of the Parthenon Sculptures or ‘Elgin Marbles’. It

comes from the west pediment of the Parthenon, and is thought to represent the

river Ilissos. To get a figure to fit the

space of a pediment’s raking cornice, you have to make it miniature or have it

recline, and once you’ve got the figure to lie, it becomes a good subject for

representing water, as it “flows” into the corner. The piece has about it that

shifting indefinable quality of breathing vitality; cold marble is made lissom

and languid by a process of almost magical alchemy and turned into warm flesh

and flowing drapery, which is then converted again into water.

Το

ιδεατό και παγκόσμιο του καιρού των μεγάλων γλυπτών της Αθήνας κατά τον 5ο

αιώνα π.Χ. γίνεται πιο προσωπικό και ρεαλιστικό την εποχή του Μεγάλου

Αλεξάνδρου, στο τέλος του 4ου αιώνα π.Χ.

Marble metope from

the Parthenon, by Pheidias. Photograph: PR

A Marble relief

(Block XLVII) from the North frieze of the Parthenon.

A figure of a naked

man, possibly Dionysos. Designed by Phidias, Athens, Greece, 438BC-432BC.

Στην

έκθεση περιλαμβάνονται και έξι από τα περίφημα Γλυπτά του Παρθενώνα, καθώς και

«θαυμαστά» δάνεια, σύμφωνα με την έκφραση του διευθυντή του Βρετανικού

Μουσείου, Νιλ ΜακΓκρέγκορ. Μεταξύ των δανείων αυτών είναι ένα εκπληκτικό

μπρούτζινο άγαλμα το οποίο ανασύρθηκε από τα νερά της Μεσογείου το 1999 και

πλέον ανήκει στην Κροατία.

Bronze statuette of

Zeus (1st-2nd century AD). This representation of the great Lord Olympus, some

20cm high, is an extraordinary piece: macho, commanding, erotically inspiring,

all the things that the male body can be. It came into the British Museum

collection in the mid 19th century having been in the collection of Dominique

Vivant Denon, the first director of the Louvre.

‘Lely’s Venus’ a

Roman copy of the lost Greek original (Royal Collection Trust/Her Majesty Queen

Elizabeth II 2015). She’s a truly exceptional piece of carving and composition

who represents the danger of getting too close to goddesses: the idea is that

you approach her from behind and you see her broad flat back, her head looking

forcefully down over her right shoulder, and her right arm reaching over her

left shoulder and seeming to play with our attention and beckon us to move

closer. So we do first a quarter turn, and then a three-quarter turn, but

finally our expectations are denied because we do not get an intimate view of

her sexual parts and instead what we get is an intimidating stare. A piece that

seems at first welcoming is in fact, very threatening.

The Belvedere Torso

(1st century BC to 1st century AD). This piece was much praised by

Michelangelo, and inspired The Creation of Adam; when asked by the Pope to

restore it, he refused on the grounds it was an inimitable work of art which,

though broken, possessed the ideal principles of Greek sculpture. I think it’s

probably a representation of Hercules, after his labours, awaiting divinity,

though there are a few different theories – there is a suggestion that he’s

Ajax – and what’s so remarkable about it is the articulation of the different

planes of the body; it’s like a cubist painting by Picasso.

«Πρόκειται

για μία από τις μεγαλύτερες αρχαιολογικές ανακαλύψεις των τελευταίων 30 ετών»,

εξήγησε ο ΜακΓκρέγκορ.

Statuette of a

veiled and masked dancer, aka the Baker Dancer (3rd-2nd century BC). It’s a

virtuoso, almost dazzling display of modelling, first of all in clay and then

cast in bronze, of a female dancer using her drapery to suggest the body

beneath, which she’s clearly very proud of. It’s a great example of the use of

drapery as sexual innuendo by sculptors in a society where the depiction of the

female body was more problematic than the male.

Marble statue of a

boy athlete, aka the Westmacott Athlete (1st century AD). This is a copy of a

lost Greek original from around the time of Socrates, and I like to think of

him as from Plato’s Charmides, a dialogue in which a beautiful boy is admired

and interrogated by Socrates, who determines that he is not only beautiful but

morally sound: he is drawn even more to him because he demonstrates “charis” or

grace. You can also see here how the sexuality of the athletic nude is reduced

by the downsizing of the genitals – and there’s no thrusting as you find with

the goal-scoring footballers of today.

«Είναι

ένας εθνικός θησαυρός και μια ευκαιρία για εμάς να δούμε πώς έμοιαζαν

πραγματικά τα ελληνικά, μπρούτζινα αγάλματα», πρόσθεσε.

LMUs Doryphoros:

Georg Römer reproduced what were regarded as the qualitatively most convincing

and best preserved elements of three Roman copies. (Snapshot of the

exhibition’s trailer)

Πραγματικά,

πολλά από τα μπρούτζινα αγάλματα έχουν εξαφανιστεί, καθώς καταστράφηκαν κατά

την αρχαιότητα επειδή είχαν μεγαλύτερη αξία ως μέταλλο παρά ως έργα τέχνης. Η

πλειονότητά τους έχει φτάσει ως την εποχή μας μέσω μαρμάρινων, ρωμαϊκών

αντιγράφων.

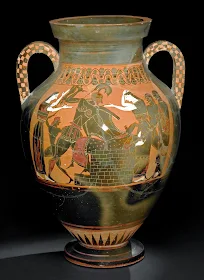

Black-figured

amphora featuring the death of Priam, 550BC-540BC. Photograph: PR

Η

έκθεση αυτή, η πρώτη μιας σειράς που έχει στόχο να επιδείξει τις μόνιμες

συλλογές του Βρετανικού Μουσείου, θα διαρκέσει ως τις 5 Ιουλίου 2015.

Defining Beauty is at the British Museum, London WC1, from March 26 to

5 July, sponsored by Julius Baer. Details: britishmuseum.org.

Απίστευτη τεχνική αρτιότητα,κατόρθωσαν να εμφυσήσουν στον μπρούτζο και στο μάρμαρο ψυχή!!!

ΑπάντησηΔιαγραφή