Βρέθηκαν 400.000 κομμάτια παπύρων γραμμένα από τους προγόνους μας και που με μια καινούργια μέθοδο μπορούν να διαβαστούν. H έγκυρη βρετανική εφημερίδα Independent σε ένα άρθρο της έγραψε: "Eureka! Εκπληκτική ανακάλυψη αποκαλύπτει τα μυστικά των αρχαίων Ελλήνων". Χιλιάδες χειρόγραφα που έως τώρα δεν μπορούσαμε να διαβάσουμε και που περιέχουν σπουδαία κείμενα της κλασσικής φιλολογίας τώρα μπορούν να διαβαστούν για πρώτη φορά με μια τεχνολογία που πιστεύεται ότι θα ξεκλειδώσει τα μυστικά των αρχαίων Ελλήνων . Μεταξύ των άλλων θησαυρών που έχουν ήδη ανακαλυφθεί από μια ομάδα επιστημόνων του Παν/μίου της Οξφόρδης υπάρχουν και άγνωστα έως τώρα έργα κλασσικών γιγάντων όπως ο Σοφοκλής, ο Ευριπίδης και ο Ησίοδος. Αόρατη με το κοινό φως η ξεβαμμένη μελάνη γίνεται καθαρά ορατή κάτω από υπέρυθρο φως με τεχνικές ανάλογες με την επισκόπηση από δορυφόρους. Τα κείμενα της Οξφόρδης αποτελούν μέρος ενός μεγάλου αριθμού παπύρων που βρέθηκαν στα τέλη του 19ου αιώνα σε έναν αρχαίο σκουπιδότοπο της ελληνο-αιγυπτιακής πόλης του Οξυρύγχου. Απομένουν χιλιάδες κείμενα να διαβαστούν μέσα στην επόμενη δεκαετία, περιλαμβανομένων έργων του Οβιδίου και του Αισχύλου. Υπάρχουν περίπου 400,000 κομμάτια παπύρων φυλαγμένα σε 800 κιβώτια στην Βιβλιοθήκη Sackler της Οξφόρδης και αποτελούν το μεγαλύτερο όγκο κλασσικών ελληνικών χειρογράφων του κόσμου. Οι ακαδημαϊκοί χαιρέτησαν με ενθουσιασμό την νέα ανακάλυψη η οποία μπορεί να οδηγήσει σε αύξηση κατά 20% των σωζόμενων ελληνικών έργων. Μέσα στα έως τώρα άγνωστα κείμενα που κατόρθωσαν να διαβάσουν με την τεχνική αυτή, περιλαμβάνονται τμήματα της χαμένης από καιρό τραγωδίας «Επίγονοι» του Σοφοκλή, μέρος μιας χαμένης νουβέλας του Έλληνα συγγραφέα Λουκιανού του 2ου αιώνα, άγνωστο κείμενο του Ευριπίδη, μυθολογική ποίηση του ποιητή Παρθένιου του 1ου αι. π.Χ, έργο του Ησίοδου του 7ου αι., και ένα επικό ποίημα του Αρχίλοχου, ενός διαδόχου του 7ου αι. του Ομήρου, που περιγράφει γεγονότα που οδήγησαν στον Τρωικό πόλεμο. «Είναι τα πιο φανταστικά νέα. Υπάρχουν δύο πράγματα εδώ. Το πρώτο είναι πόσο φοβερά επηρέαζαν τις επιστήμες και τις τέχνες οι Έλληνες. Το δεύτερο είναι πόσο λίγα από τα γραπτά τους σώζονται » λένε οι Άγγλοι επιστήμονες.

Ancient texts

obscured for millennia can now be read through infrared technology. A display

in the Hinckley Center depicts the innovative multispectral imaging work of BYU

scholars. Photo by Mark

Philbrick

Two thousand years

ago, Oxyrhynchus, "city of the sharp-nosed fish," was a provincial

capital in central Egypt populated by the well-educated descendants of Greek

settlers. It had an 11,000-seat theater, a religious cult dedicated to the

city's namesake -- and a municipal dump on the outskirts of town. People

discarded trash there and probably never gave it a thought, and over the years

the mound grew to a height of 30 feet. When archaeologists excavated it at the

turn of the 20th century, they found a treasure more precious than gold. Buried

in the dump were more than 400,000 fragments of papyrus -- bits of documents,

pieces of scrolls and pages from old books written between the 2nd century B.C.

and the 8th century A.D. and preserved ever since in the hot, dry climate. For

years, scholars have been trying to decipher these texts, which include

property records, epistles from the New Testament, writings from early Islam

and fragments of unknown works by the giants of classical antiquity. The pace

of discovery has been painstaking, but this year scientists brought an

innovative imaging technology to the fragments, enabling them to peer though

the grime of centuries to see previously invisible script while leaving the

crumbling papyrus undamaged. The technology, multispectral imaging, has

dramatically increased the recovery rate. In a pass through a collection of

Oxyrhynchus papyri at Oxford University's Sackler Library last month, scholars

turned up tantalizing new bits of lost plays by Euripides, Sophocles and

Menander and lost lines from the poets Sappho, Hesiod and Archilochus.

"It's one of the most exciting things we've ever done," said Roger T.

Macfarlane, a classicist at Brigham Young University. "There are pieces of

papyrus that have gesso [a plaster] over the text, but with the filters it's

almost like X-ray vision." A BYU team led by Macfarlane has been using

multispectral imaging since 1999, and it turned to the Oxyrhynchus fragments

after focusing first on the spectacular Villa of the Papyri, an entire Roman

library roasted in place during the fabled eruption of Mount Vesuvius that destroyed

the towns of Herculaneum and Pompeii in A.D. 79. Between them, the charred

Herculaneum scrolls and the Oxyrhynchus trash are the world's two largest known

repositories of previously unread ancient manuscripts -- a collection of

staggering potential. "We have seven plays by Sophocles, and there are

about 90 missing. Euripides wrote 100 plays and Menander about 70," said

Richard Janko, a classicist at the University of Michigan. "Herculaneum is

the only place in the ancient world where a library has been buried, and the

garbage dump is almost as good." Multispectral imaging was developed by

NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory to allow telescopes to peer through shrouds of

dust and gas, and to reveal the surfaces of distant planets. By using different

filters, the instrument can ignore irrelevant light frequencies and focus on

the target object. Working with Gene Ware, an emeritus electrical engineer at

BYU, Macfarlane's team produced remarkable results with the Herculaneum scrolls

as it scanned in infrared and near-infrared frequencies, causing what are

opaque surfaces to the naked eye to blossom suddenly with hidden script. Many

of the scrolls had been lovingly unrolled, while others were unforgivably torn

apart by discoverers and early archivists to get at the text, but Macfarlane's

basic task was the same for all -- use the imager to read black on black. The

scrolls had been cooked in place during the eruption, like rolled-up newspapers

trapped in an oven. Oxyrhynchus presented a different set of problems.

"The fragments have been darkened from light brown to dark dirty brown,

covered with soil, sand, mud and paint, and eaten by salt, insects and God

knows what else," said papyrologist Dirk Obbink, director of the recovery

efforts. Also, the material from Oxyrhynchus, unlike Herculaneum's, "is

what people throw away," Obbink said in a telephone interview. "There

are private papers, public records, and pieces of Menander and Sophocles.

Finding a page from a book is typical." Obbink, who holds appointments at

both Oxford and the University of Michigan, is a leading authority on ancient

classics and conservation. He won a 2001 MacArthur Fellowship for his work at

both Oxyrhynchus and Herculaneum. In 1996, he reconstructed Philodemus's

"On Piety," a treatise on the gods and religion, from seemingly

disparate pieces of the Herculaneum scrolls. At Oxyrhynchus, Obbink is trying

to repeat this achievement by recovering Hesiod's "Catalogue of

Women," a genealogy describing the love affairs of gods with mortals and

the offspring they produced. "We have so many pieces now that the text can

be said to exist," Obbink said. "There are a lot of gaps, but you can

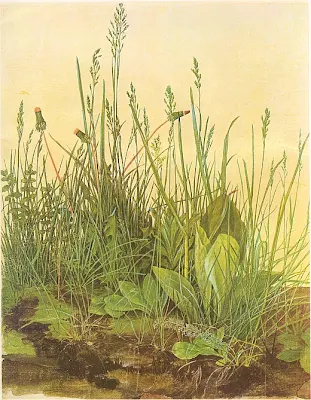

read it." Unlike in the European Middle Ages, when books were made of

animal hide parchment so costly that virtually no one but the very rich could

own one, ordinary citizens had access to papyrus -- the leaf of a common plant

-- and they might buy a scroll or, after the 4th century, a loose-leaf book

known as a codex. "There was access to literacy during the Roman period,

and many people at least could write their names in their personal

dealings," Obbink said. "Some women were literate and were teaching

school." Evidence for all of this can be found in the dump. Obbink said

the largest percentage of literary texts at Oxyrhynchus is made up of fragments

of Homer, whose archaic Greek was taught in school to hone language skills.

Euripides, Sophocles and Menander were popular authors read for amusement, and

when the flimsy pieces started to give way, readers tore off the damaged ones,

used the margins for writing notes to themselves and then tossed them in the

trash. It worked the other way, too. Literary texts frequently appeared on the

backs of recycled personal documents. Obbink and his colleagues have found a

variety of languages and scripts in the fragments. Besides Greek and Latin,

they include Hieratic (cursive hieroglyphs), Demotic (hieroglyphic shorthand),

Coptic (Egyptian with the Greek alphabet), Aramaic, Hebrew, Persian, Old

Nubian, Syriac and, in the later deposits, Arabic. Obbink is going through 725

boxes of material to pick out the promising fragments, which are assigned to

students "who translate them and try to figure them out," he said.

"It's part of learning Greek and Latin, and it sharpens your editing

skills."

,+Los+Angeles,+The+Museum+of+Contemporary+Art+(2).jpg)

++Huile+sur+Toile++++197,5x166,4++Collection+Alter+(2).jpg)