Every so often, a

series of photographs changes the way we look at the world. When Collier Books

published Philip Jones Griffiths' Vietnam Inc. in 1971, the book was a

revelation and, for Jones Griffiths, a labour of both love and revenge.

Philip Jones

Griffiths was born in 1936 in the Welsh village of Rhuddlan near Rhyl in

Flintshire. Growing up during a time when the great picture magazines – Life,

Illustrated and Picture Post – were producing powerful picture stories, he

became fascinated by photo-reportage and its ability to open a window on the

world. He taught himself photography and before long was photographing weddings

in his home town.

For the group of

photographers who congregated around Jones Griffiths in the early 1960s, the

London scene was an exciting one. At the Institute for Contemporary Arts there

was considerable interest in the new documentary photography, and a recent

touring Cartier Bresson exhibition caused much interest, as had the large-scale

"Family of Man" show at the Royal Festival Hall.

Photographers were

central characters on the post-war arts and media scene – John Deakin was active

as a portraitist in Soho, Roger Mayne was establishing himself as London's

foremost social documentarist and most of the Picture Post photographers were

still working. David Bailey and Terence Donovan would soon become not just

successful fashion photographers, but media celebrities, as they brought a new

street style into fashion magazines. Men's magazines such as Queen employed the

new photographers and gave their pictures space and dignity. In 1964, The

Observer launched its own colour supplement, and Jones Griffiths, already on

staff, became a central photographer.

Documentary

photography was very much the vogue, and from the late 1950s, Jones Griffiths

was travelling around Britain to record a country still in a state of post-war

dereliction.

The new weekend

supplements, plus the older US magazines such as Life, gave photojournalists

ample opportunities to document the war zones. Don McCullin's story, for The

Sunday Times, on the famine in Biafra has become the stuff of journalistic

legend, and in Vietnam, Philip Jones Griffiths consolidated his reputation as

an incisive and committed photojournalist.

Jones Griffiths had

always been an acute social critic, and gravitated to the left. Like many of

the younger photographers in Vietnam, he questioned the U S presence in

South-east Asia, and took the military media managers by surprise. Those who

had expected the journalistic contingent to be "on side" were

horrified by the critical reports and revealing photo stories that began to

appear in mainstream publications across the world and were unable to control

the output of energetic reporters who, as the war continued, arrived in Saigon

by the score.

The most powerful

written memories of the war in Vietnam came from Michael Herr in his reports

for Rolling Stone magazine, but the most acute photographic statement was

undoubtedly made by Jones Griffiths, who spent three years reporting from the

country. He was passionate about the plight of the Vietnamese and as well as

making photographs he also compiled data about the depredations of the

Vietnamese economy. His book Vietnam Inc. (reportedly funded by the proceeds of

a set of photographs of Jackie Kennedy holidaying in Cambodia) was an instant

success. As well as taking the photographs, Jones Griffiths had written the

detailed and acerbic text, a series of extended picture captions, which

powerfully expressed the photographer's anger and despair.

In Vietnam Inc.,

Jones Griffiths showed children in burnt-out villages, captured Viet Cong under

interrogation, families held at gunpoint by the US Marines, dead children,

blood-soaked babies, Saigon brothels, girl prostitutes, all against the

background of a beautiful and primarily rural country. He also photographed the

Marines, bewildered and confused, lashed by the monsoon, wading their way

through the rice fields and the jungle, fighting a war which, for most of them,

had no rhyme or reason.

And, along the way,

he made a valuable document of the increasing use of high technology by the US

military, the emergence of the computer, the beginning of management speak.

Jones Griffiths was particularly fascinated by the military's clumsy attempts

to become involved in the complex Vietnamese social structure.

To expect

foreigners to be able to tune into this complexly structured existence, even

when afforded every encouragement, is to be highly optimistic, especially in

the case of the Americans whose alienation as a group from the Vietnamese is

extreme; but, when the society as a whole is actively using every means

possible to prevent its happening, the expectation is wildly unrealistic.

So, what the

previous American administration should have asked itself is, whether or not to

become involved in revolutionising (and simultaneously being exploited by) a

people with whom it could not communicate: whether or not Americans should

attempt to win the hearts and minds of a people who never reveal their desires

or aspirations: whether or not it would be feasible to co-operate with a people

who have a language that is impossible to speak and difficult to read even with

the aid of a dictionary or phrase book . . . To put it another way, was it fair

to send American boys to a country where they have twenty-five different ways

of pronouncing the word "Ma"?

Vietnam Inc. was

arguably the most important photo book of the 1970s. Its first printing sold

out quickly, and has since become one of the most sought-after photography

books of our time. (It was finally reissued, 30 years later, in 2001). Though

its influence as a catalyst of political change is debatable, its importance

within photoreportage cannot be underestimated.

For the young

photographers emerging onto the independent scene in the 1970s, Vietnam Inc.

epitomised the power of photography and the photo book and pointed to the

emerging status of the photographer as author, rather than as the "other

half" of a journalistic team. Together with Don McCullin's The Destruction

Business (1971), The Concerned Photographer (1972) by Cornell Capa, David

Douglas Duncan's War Without Heroes (1970) and Larry Burrows' Compassionate

Photographer (1972), Vietnam Inc. was a central part of the new wave of photo

books in which the photographer's personal experience was central.

The idea of the

concerned photographer as a contemporary figure became the core of photographic

practice in Europe and the US. The young men (and a very few women) who were

embarking on their photographic education at the beginning of the 1970s saw

these books as models for their own practice, even when their work took them no

further than the north east of England or the English seaside. The immediacy

and passion of Vietnam Inc., together with its trenchant early warning about

the dangers of globalisation and US imperialism, set Jones Griffiths apart from

most of the English photojournalists who had worked alongside him in the UK,

and established him as a much-revered figure.

In 1971 Jones

Griffiths joined the photographers' co-op Magnum, which had been set up by

Robert Capper, Henry Cartier Bresson and George Rodger at the end of the Second

World War. With the demand for high-quality photojournalism from magazines and

galleries, Magnum was riding high as the dominant power in the photography

market, with a status that elevated its members far above the press pack. The

war photographer became a heroic figure in the public imagination and

photographers such as Don McCullin became celebrities.

Magnum protected

the interests of its members with ferocity and, as well as editorial work, the

photographers received lucrative commissions from the corporate world to

provide the visuals for company reports and increasingly, for advertising. But

however many bargains Magnum and its photographers struck with the world of business,

the public face of the agency was always that of high-minded, conscience-driven

photoreportage, promoted through books and exhibitions, as well as through

magazine pieces.

For Philip Jones

Griffiths, and the other British photographers who joined around the same time,

Magnum was the perfect home. Although noted for its tempestuous annual meetings

and the arguments around who should or shouldn't be allowed to join (Jones

Griffiths was bitterly opposed to Martin Parr's membership and refused even to

speak to Parr after he was finally allowed to join), it has been a remarkably

successful and influential organisation and Jones Griffiths played a pivotal

part in the agency throughout the next three decades, serving as president for

five years from 1980.

He continued to

make photojournalism for the rest of his life, though, based in New York from

1980, he was not a familiar figure on the British scene. He retained his

passionate attachment to South-east Asia but also made photographs in Algeria,

Northern Ireland, Lebanon, Kuwait and Bosnia. Vietnam Inc. was perhaps a curse

as well as a blessing for, despite all the work he produced after its

publication, his name would always be linked to this work.

The images which

Philip Jones Griffiths made in Vietnam in the late 1960s have remained a

cornerstone of the post-war photojournalistic achievement. Passionate,

partisan, campaigning, they challenged notions of objectivity and distance, and

proclaimed that the photographer was a witness rather than an observer, a taker

of testaments and a grave giver of warnings.

He continued to

make photographs, despite illness, publishing Agent Orange in 2004 and Viet Nam

at Peace in 2005. At the time of his death, he was working on Recollections, a

collection of his photographs of British life and society from the 1950s to the

1970s.

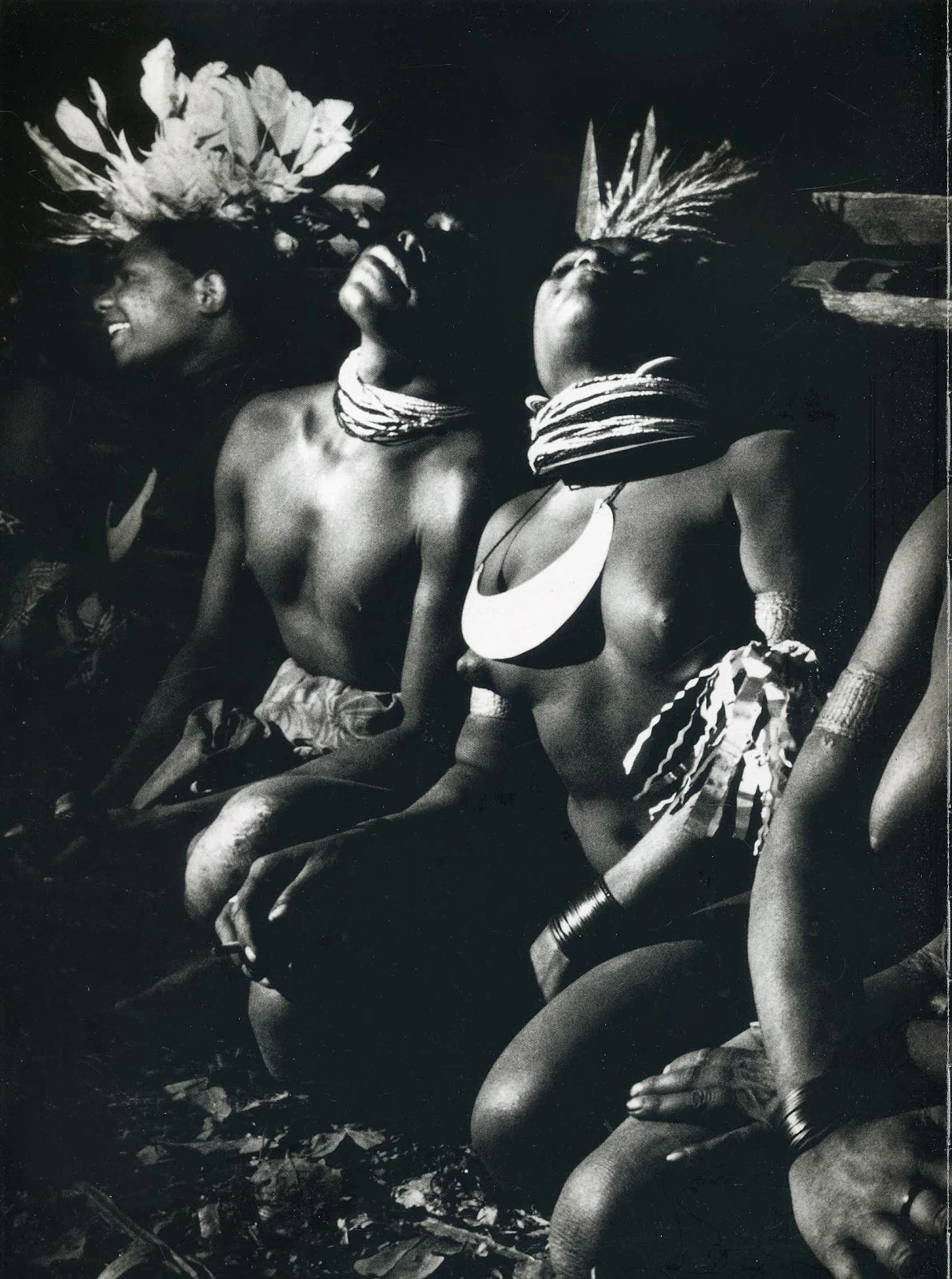

Philip Jones

Griffiths' eagerly anticipated retrospective, "Dark Odyssey" traces his forty-year journey through this

chaotic world, from his native Wales to the ravaged villages of war-torn

Vietnam, through Europe, Africa, and Asia, in more than one hundred

black-and-white photographs. The collision of culture and ideology is often the

basis of Griffiths' work, sometimes in simple pairings of figures, other times

in a dizzying throng of life. Love, death, frivolity, politics, violence; the

images in "Dark Odyssey"

(the first collection since Griffiths' acclaimed "Vietnam Inc." in 1971) comment on virtually every aspect of

human life, offering a gripping and unforgettable view of both the beauty and

devastation of our era.

Πηγή:

The Independent