Η

περίοδος 1900-1918 για τη φωτογραφία σημαίνει μετάβαση από τις παραδόσεις του

1800 στις καινοτομίες του 1900. Για τους εφευρέτες της φωτογραφίας πιο

σημαντικό ήταν να αναπτύξουν ένα μηχανικό τρόπο απεικόνισης από το να

δημιουργήσουν ένα νέο καλλιτεχνικό μέσο έκφρασης. Έτσι η ζωγραφική αποτέλεσε

για πολύ καιρό το πρότυπο της φωτογραφίας και η προσπάθεια των φωτογράφων

περιοριζόταν στη δημιουργία φωτογραφιών που έμοιαζαν με έργα ζωγραφικής.

Παράλληλα υπήρξαν προσπάθειές να καθιερωθεί η φωτογραφία σαν αυτόνομη τέχνη, γεγονός που δε βρήκε ευρεία αποδοχή παρά μόνο μετά το 1918.

Μετά

τον Α' Παγκόσμιο Πόλεμο μια νέα γενιά φωτογράφων απομακρύνθηκε από το ζωγραφικό

στυλ και πήρε ριζικά διαφορετικές κατευθύνσεις. Μερικοί από αυτούς τους νέους

καλλιτέχνες ασπάζονται τις αισθητικές αρχές των ριζοσπαστικών κινημάτων - ντανταϊσμός,

φουτουρισμός, σουρεαλισμός, κονστρουκτιβισμός - άλλοι ήταν πιο «συντηρητικοί».

Αλλά όλοι μοιράζονται την πεποίθηση ότι η φωτογραφία παρείχε την κατάλληλη

τεχνολογία και τις μεθόδους για να καταγράψει τη σύγχρονη ζωή. Πράγματι, πολλά

από τα προοδευτικά επιτεύγματα στη φωτογραφική τέχνη της δεκαετίας του μεσοπολέμου

οφείλονται κατά ένα μεγάλο μέρος στα φωτογραφικά τους οράματα.

After the war a new

generation of photographers turned from painterly styles and took radically

different directions. Some of these young artists espoused the aesthetic

principles of avant-garde movements—dadism, futurism, surrealism,

constructivism; others were unaligned. But they all shared the belief that

photography provided the appropriate technology and methods to record modern

life. Indeed, much of the most progressive art of the 1920s and 1930s owes a

great debt to their photographic visions.

Although photography

is now the most ubiquitous and generally accessible of modern art media, it is

not widely recognized that many of its forms—which today seem most new and

which have been borrowed by modern painters—were discovered and creatively

explored over half a century ago. Indeed, the photographs of the interwar

period lie at the origin of our culture's visual sense of itself. These

pictures are intriguing and often beautiful; if their lessons are not always

easy, we are confident that the viewers' efforts will bring rich rewards.

Artists:

Abbott, Berenice

(American, 1898–1991) | Adams, Ansel (American, 1902–1984) |

Bayer, Herbert (American, born Austria, 1900–1985) |

Brassaï (Gyula Halász) (French, born Hungary, 1899–1984) |

Cartier-Bresson, Henri (French, 1908–2004) | De

Zayas, Marius (Mexican, 1880–1961)

| Evans, Walker (American,

1903–1975) | Heartfield, John (German, 1891–1968) |

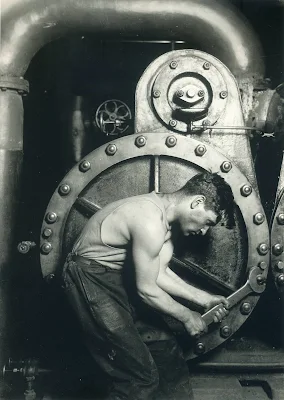

Hine, Lewis W. (American, 1874–1940)

| Kandinsky, Vasily (French, born

Russia, 1866–1944) | Lange, Dorothea (American, 1895–1965) |

Moholy, Lucia (British, born Czechoslovakia, 1894–1989) |

Moholy-Nagy, László (American, born Hungary, 1895–1946) | Mole,

Arthur (American) | Munkacsi, Martin (American, born Hungary,

1896–1963) | Picabia, Francis (French, 1879–1953) |

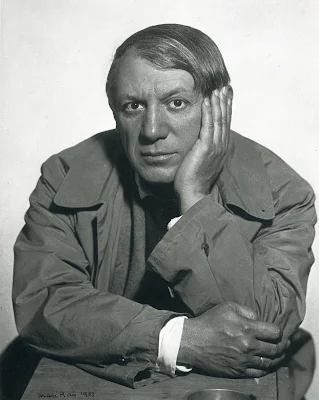

Picasso, Pablo (Spanish, 1881–1973)

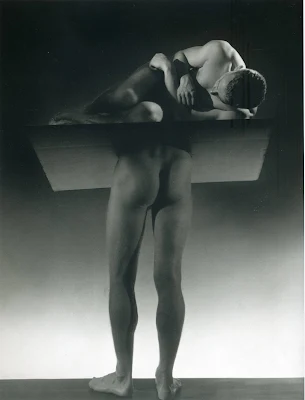

| Ray, Man (American,

1890–1976) | Renger-Patzsch, Albert (German, 1897–1966) |

Rodchenko, Aleksandr (Russian, 1891–1956) |

Sander, August (German, 1876–1964)

| Schamberg, Morton (American,

1881–1918) | Shahn, Ben (American, born Lithuania,

1898–1969) | Sheeler, Charles (American, 1883–1965) |

Siegel, Arthur (American, 1913-1978)

| Steichen, Edward (American,

born Luxembourg, 1879–1973) | Stieglitz, Alfred (American, 1864–1946) |

Strand, Paul (American, 1890–1976)

| Tabard, Maurice (French,

1897–1984) | Thomas, John D. (American) |

Weston, Edward (American, 1886–1958)

| White, Clarence H. (American,

1871–1925)