Odysseus, in the

guise of a beggar, tries to be recognized by Penelope. Terracotta relief, ca.

450 BC. From Milo. Ulysse déguisé en mendiant tente de se faire reconnaître par

Pénélope. Relief en terre cuite, vers 450 av. J.-C. Provenance: Milo.

Δεν

ήτανε πως δεν τον γνώρισε στο φως της παραστιάς· δεν ήταν

τα

κουρέλια του επαίτη, η μεταμφίεση, – όχι· καθαρά σημάδια:

η

ουλή στο γόνατό του, η ρώμη, η πονηριά στο μάτι.

Max Klinger, Penelope, 1896

Τρομαγμένη,

ακουμπώντας τη ράχη της στον τοίχο,

μια

δικαιολογία ζητούσε,

μιά

προθεσμία ακόμη λίγου χρόνου,

να

μην απαντήσει,

να

μην προδοθεί.

Honoré Daumier, Ulysses and Penelope, Lithograph, 1842

Γι’

αυτόν, λοιπόν, είχε ξοδέψει είκοσι χρόνια,

είκοσι

χρόνια αναμονής και ονείρων, για τούτον τον άθλιο,

τον

αιματόβρεχτο ασπρογένη;

Marc Chagall, Ulysses and Penelope, 1975

Ρίχτηκε

άφωνη σε μια καρέκλα,

κοίταξε

αργά τους σκοτωμένους μνηστήρες στο πάτωμα,

σαν

να κοιτούσε νεκρές τις ίδιες τις επιθυμίες.

Και:

«καλώς όρισες», του είπε,

ακούγοντας

ξένη, μακρινή, τη φωνή της.

John William

Waterhouse, Penelope and the Suitors,

1912

Στη

γωνιά, ο αργαλειός της γέμιζε το ταβάνι με καγκελωτές σκιές·

κι

όσα πουλιά είχε υφάνει με κόκκινες λαμπρές κλωστές σε πράσινα φυλλώματα,

αίφνης,

τούτη τη νύχτα της επιστροφής, γυρίσαν στο σταχτί και μαύρο

χαμοπετώντας

στον επίπεδο ουρανό της τελευταίας της καρτερίας.

Λέρος,

21.ΙΧ.68

Από

την ποιητική συλλογή: «Επαναλήψεις, σειρά ΙΙ» (1968 / 1972).

Penelope's Despair

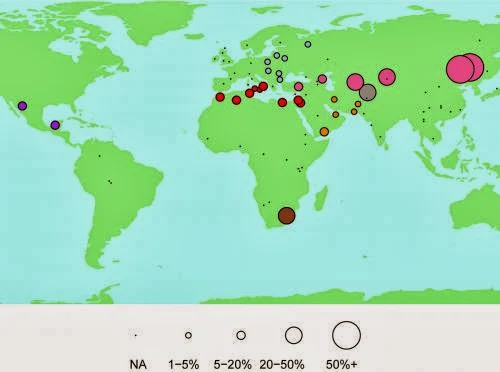

A Roman

wall-painting from the first century ce, showing Penelope contemplating the

stranger and pondering, while Eurycleia looks on from the doorway (upper left).

It wasn't that she

didn't recognize him in the light from the hearth: it wasn't the beggar's rags,

the disguise–no. The signs were clear: the scar on his knee, the pluck, the cunning

in his eye. Frightened, her back against the wall, she searched for an excuse, a

little time, so she wouldn't have to answer, give herself away.

David Byers Brown, Odysseus and Penelope. As his faithful

followers dance to delay news of the massacre reaching the Ithacan town,

Odysseus recounts his travels to his wife Penelope. Pencil on A4 card signed

and dated 26th-27th July 2008.

Was it for him,

then, that she'd used up twenty years, twenty years of waiting and dreaming,

for this miserable blood-soaked, white-bearded man?

She collapsed voiceless into a chair, slowly studied the slaughtered suitors on the floor as though seeing her own desires dead there. And she said "Welcome," hearing her voice sound foreign, distant.

Benton Spruance, Penelope, Color Lithograph, 1956

In the corner, her

loom covered the ceiling with a trellis of shadows; and all the birds she'd

woven with bright red thread in green foliage, now, on this night of the return,

suddenly turned ashen and black, flying low on the flat sky of her final

enduring.

Translated by Edmund Keeley

ΓΙΑΝΝΗΣ

ΡΙΤΣΟΣ

"Yannis

Ritsos," wrote Peter Levi in the Times Literary Supplement of

the late Greek poet, "is the old-fashioned kind of great poet. His output

has been enormous, his life heroic and eventful, his voice is an embodiment of

national courage, his mind is tirelessly active." At their best, Ritsos'

poems, "in their directness and with their sense of anguish, are moving,

and testify to the courage of at least one human soul in conditions which few

of us have faced or would have triumphed over had we faced them," as

Philip Sherrard noted in the Washington Post Book World. Twice

nominated for the Nobel Prize, Ritsos won the Lenin Peace Prize, the former

Soviet Union's highest literary honor, as well as numerous literary prizes from

across Eastern Europe prior to his death in 1990.

The hardship and misfortune of Ritsos' early life played a large role in all of

his later writings. His wealthy family suffered financial ruin during his

childhood, and soon afterward his father and sister went insane. Tuberculosis

claimed his mother and an older brother and later confined Ritsos himself to a

sanatorium in Athens for several years. Poetry and the Greek communist movement

became the sustaining forces in his life.

Because his writing was frequently political in nature, Ritsos endured periods

of persecution from his political foes. One of his most celebrated works, the

"Epitaphios," a lament inspired by the assassination of a worker in a

large general strike in Salonica, was burned by the Metaxas dictatorship, along

with other books, in a ceremony enacted in front of the Temple of Zeus in 1936.

After World War II and the annihilation of Greece's National Resistance

Movement—a Communist guerrilla organization that attempted to take over the

country in a five-year civil war—Ritsos was exiled for four years to the

islands of Lemnos, Makronisos, and Ayios Efstratios. His books were banned

until 1954. In 1967, when army colonels staged a coup and took over Greece,

Ritsos was again deported, then held under house arrest until 1970. His works

were again banned.

Ritsos' poetry ranges from the overtly political to the deeply personal, and it

often utilizes characters from ancient Greek myths. One of his longer works and

the subject of several translations, The Fourth Dimension, is

comprised of seventeen monologues that most frequently involve the ancient King

Agamemnon and the tragic House of Atreus. Narrated by such classical figures as

Persephone, Orestes, Ajax, Phaedra, and Helen of Troy, The Fourth

Dimension is a "beautifully written book . . . describing what

happens when love and hate and sibling rivalry run amok," commented Standreviewer

Mary Fujimaki, who also praised the work's "colour, the excitement, the

shifting back and forth from past to present that naturally makes the stories

seem more familiar to modern readers." Shorter in length are the verses

from 1991's Repetitions, Testimonies, Parentheses, a collection of

eighty relatively brief poems that incorporate Greek myths and history.

"Here . . . is the Ritsos of 'simple things,'" commented Minas Savvas

in a review for World Literature Today. "The desire to

draw out a moment or an object and magically expand it for its mystifying,

arcane significance is wonderfully evident in these laconic, almost

epigrammatic poems."

Many critics rank Ritsos' less political poems as his best work. George Economou,

writing in the New York Times Book Review, stated that

"in the short poems, most of which are not overtly political, Ritsos is

full of surprises. He records, at times celebrates, the enigmatic, the

irrational, the mysterious and invisible qualities of experience." Vernon

Young in Hudson Review cited Ritsos' "remarkable gift . .

. for suggesting the sound and color of silence, the impending instant, the

transfixed hush." Similarly, John Simon pointed to the surreality of

Ritsos' work. In a review of Ritsos in Parenthesis for Poetry, Simon

wrote: "What I find remarkable about Ritsos' poetry is its ability to make

extraordinary constructs out of the most unforcedly ordinary

ingredients—surreality out of reality. And seem not even to make it, just find

it." Simon also found a loneliness in Ritsos' poems. He explained:

"Ritsos . . . is also a great bard of loneliness, but of loneliness

ennobled and overcome. Poem after poem, image upon image, suffuses aloneness

with a gallows humor that begins to mitigate its ravages and makes the person

in the poem a Pyrrhic winner." Ritsos' final volume of verse, Argha,

poli argha mesa sti nihta, was completed just prior to his death and

published in its original Greek in 1991. "The imagistic dynamism, lyric

intensity, and astonishing quasi-surrealistic expressions" that

characterized the poet's work for his seventy-year career are, in the opinion

of World Literature Today reviewer M. Byron Raizis,

"manifest again, as refreshing and effective as any time during . . . his

creative activity."

..jpg)