Andy Goldsworthy is

a brilliant British artist who collaborates with nature to make his creations.

Besides England and Scotland, his work has been created at the North Pole, in

Japan, the Australian Outback, in the U.S. and many others.

Goldsworthy regards

his creations as transient, or ephemeral. He photographs each piece once right

after he makes it. His goal is to understand nature by directly participating

in nature as intimately as he can. He generally works with whatever comes to

hand: twigs, leaves, stones, snow and ice, reeds and thorns.

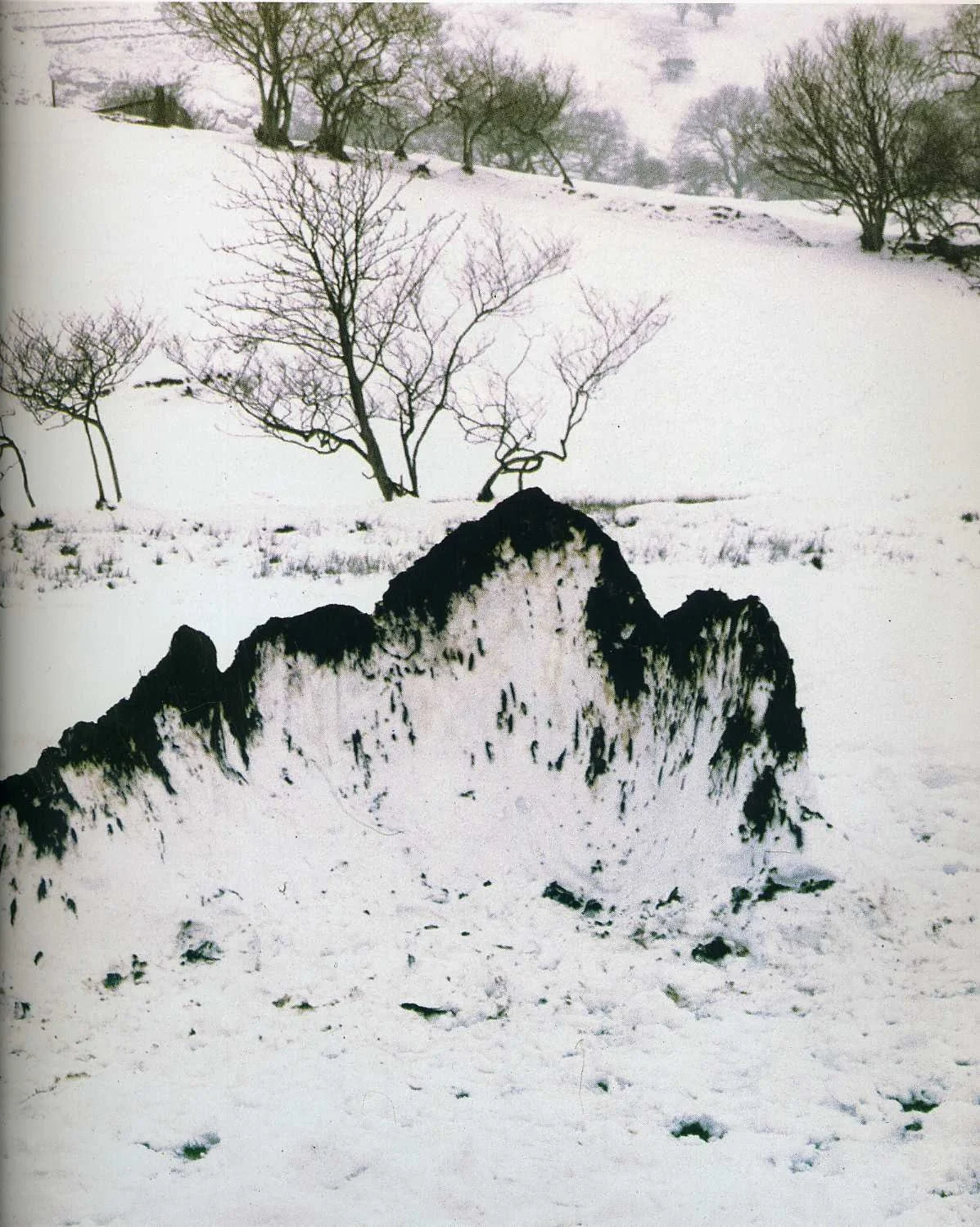

On a typical autumn

day, Andy Goldsworthy can be found in the woods near his home in Penpont,

Scotland, maybe cloaking a fallen tree branch with a tapestry of yellow and

brown elm leaves, or, in a rainstorm, lying on a rock until the dry outline of

his body materializes as a pale shadow on the moist surface. Come winter, he

might be soldering icicles into glittering loops or star bursts with his bare

fingers. Because he works outdoors with natural materials, Goldsworthy is

sometimes portrayed as a modern Druid; really, he is much closer to a

latter-day Impressionist.

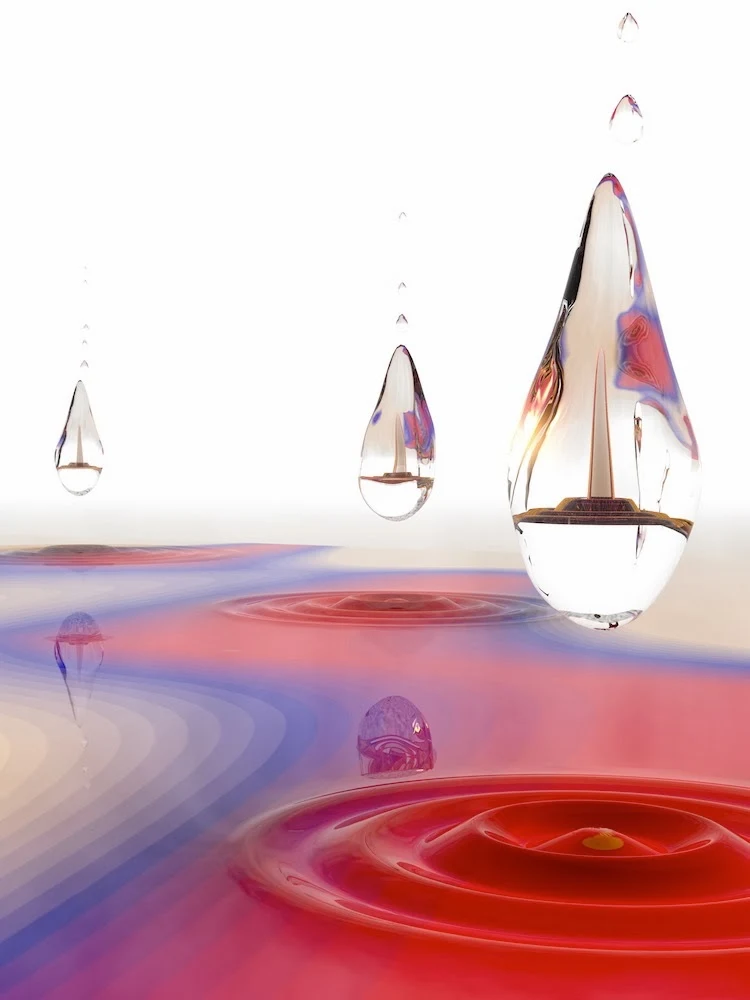

Like those

19th-century painters, he is obsessed with the way sunlight falls and flickers,

especially on stone, water and leaves. Monet—whose painting of a sunrise gave

the Impressionist movement its name—used oil paint to reveal light's

transformative power in his series of canvases of haystacks, the Rouen

Cathedral and the Houses of Parliament. Goldsworthy is equally transfixed with

the magical effect of natural light. Only he has discovered another, more

elemental way to explore it.

As a fine arts

student at Preston Polytechnic in northern England, Goldsworthy, disliked

working indoors. He found escape nearby at Morecambe Bay, where he began

constructing temporary structures that the incoming tide would collapse. Before

long, he realized that his artistic interests were tied more closely to his

youthful agricultural labors in Yorkshire than to life classes and studio work.

The balanced boulders, snow arches and leaf-rimmed holes that he crafted were

his versions of the plein-air sketches of landscape artists. Instead of

representing the landscape, however, he was drawing on the landscape itself.

Throughout the 20th

century, artists struggled with the dilemma of Modernism: how to convey an

experience of the real world while acknowledging the immediate physical reality

of the materials—the two-dimensional canvas, the viscous paint—being used in

the representation. Goldsworthy has cut his way clear.

By using the

landscape as his material, he can illustrate aspects of the natural world—its

color, mutability, energy—without resorting to mimicry. Although he usually

works in rural settings, his definition of the natural world is expansive.

"Nature for me isn't the bit that stops in the national parks," he

says. "It's in a city, in a gallery, in a building. It's everywhere we are."

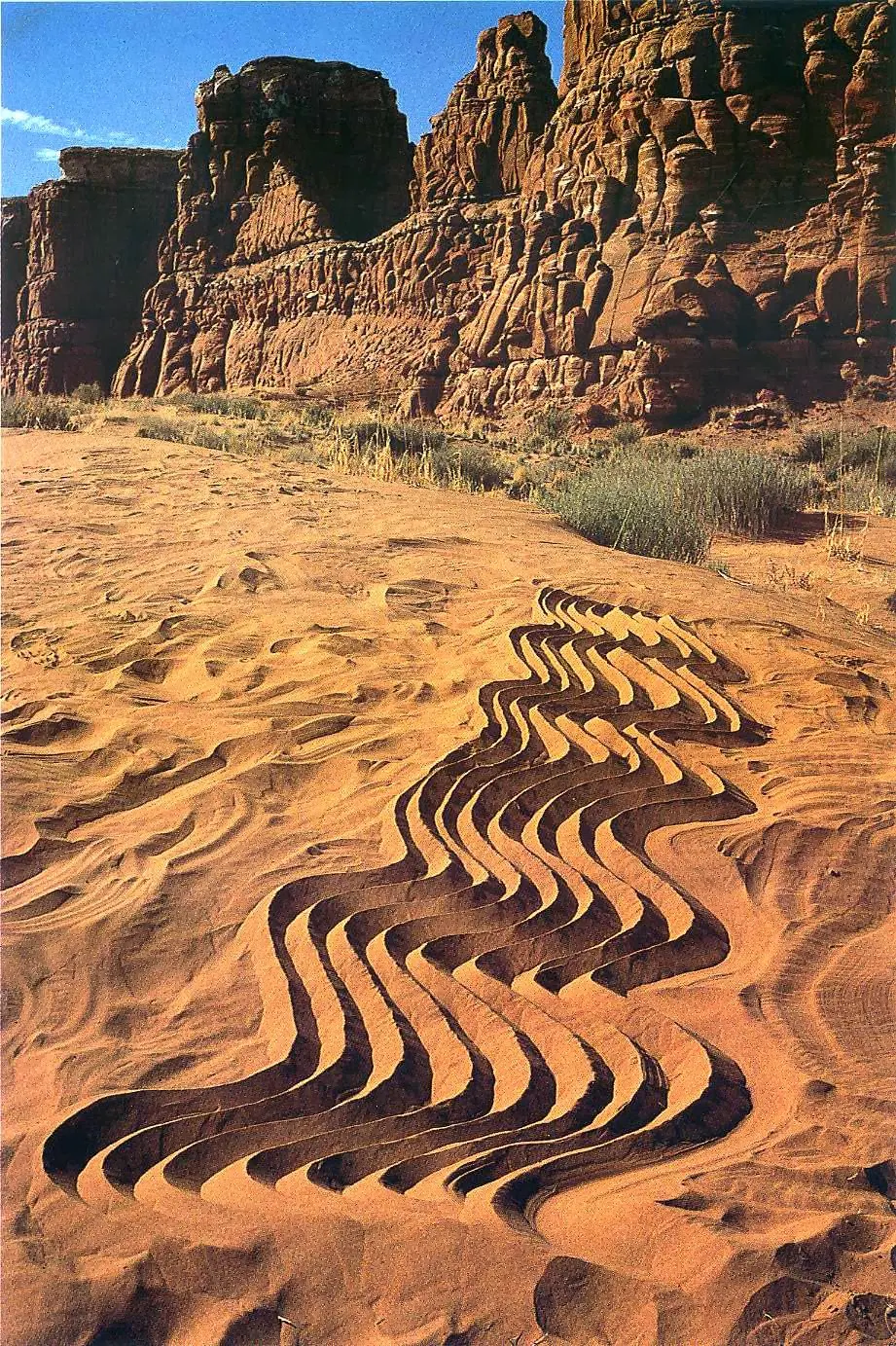

Goldsworthy's principal

artistic debt is to "Land Art," an American movement of the 1960s

that took Pollock's and de Kooning's macho Abstract Expressionism out of the

studio to create giant earthworks such as Robert Smithson's Spiral Jetty in the

Great Salt Lake of Utah or Michael Heizer's Double Negative in Nevada. Unlike

Smithson and Heizer, however, Goldsworthy specializes in the ephemeral.

A seven-foot-long

ribbon of red poppy petals that he stuck together with saliva lasted just long

enough to be photographed before the wind carried it off. His leaves molder,

his ice arabesques melt. One work in which he took special joy, a sort of

bird's nest of sticks, was intended to evoke a tidal whirlpool; when the actual

tide carried it into the water, its creator marveled as it gyrated toward

destruction.

The moment was

captured in Rivers and Tides, a documentary film by Thomas Riedelsheimer that

portrayed Goldsworthy at work and underscored the centrality of time to his

art.

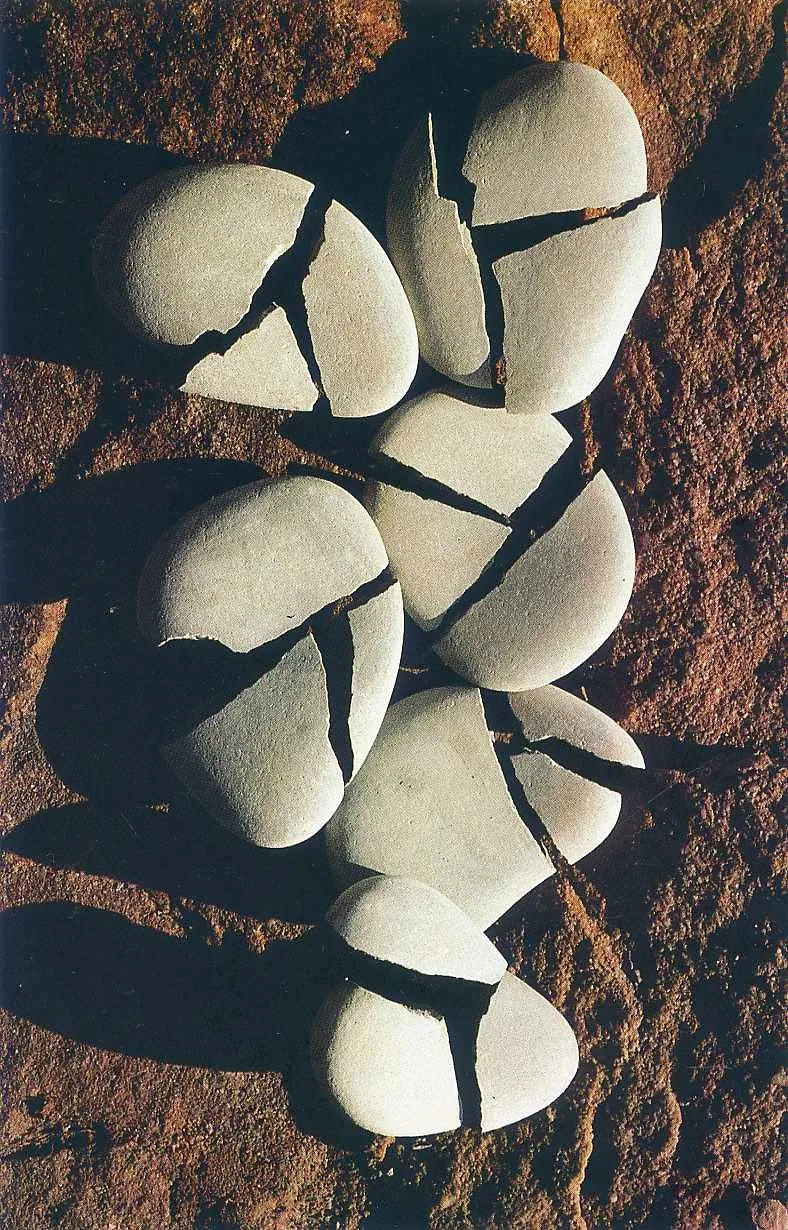

Even those stone

stacks and walls that he intends to last for a long time are conceived in a

very different spirit from the bulldozing Land Art of the American West. An

endearing humility complements his vast ambition. "There are occasions

when I have moved boulders, but I'm reluctant to, especially ones that have

been rooted in a place for many years," he says, noting that when he must

do so, he looks "for ones on the edge of a field that had been pulled out

of the ground by farming. The struggle of agriculture, of getting nourishment

from the earth, becomes part of the story of the boulder and of my work."

The modesty in his

method is matched by a realism in his demands. He knows that nothing can or

should last forever. Once a piece has been illuminated by the perfect light or

been borne away by the serendipitous wave, he gratefully bids it a fond

farewell.

© Andy Goldsworthy.

All copyright remains with the Artist.

Using an endless

range of natural materials—snow, ice, flowers, leaves, icicles, mud,

pine-cones, stones, twigs, thorns, bark, rock, clay, feathers, petals,

twigs—Andy Goldsworthy creates outdoor artwork that is usually transient and

disappear shortly after creation. Just before they disappear, he takes

photographs of his work.